Few people have ever heard of the tiny country of Nauru. Even fewer ever think about what happens at the bottom of the world’s oceans. But that may soon change. The seafloor is thought to hold trillions of dollar’s worth of metals and this Pacific-island nation is making bold moves to get a jump on the global competition to plumb these depths.

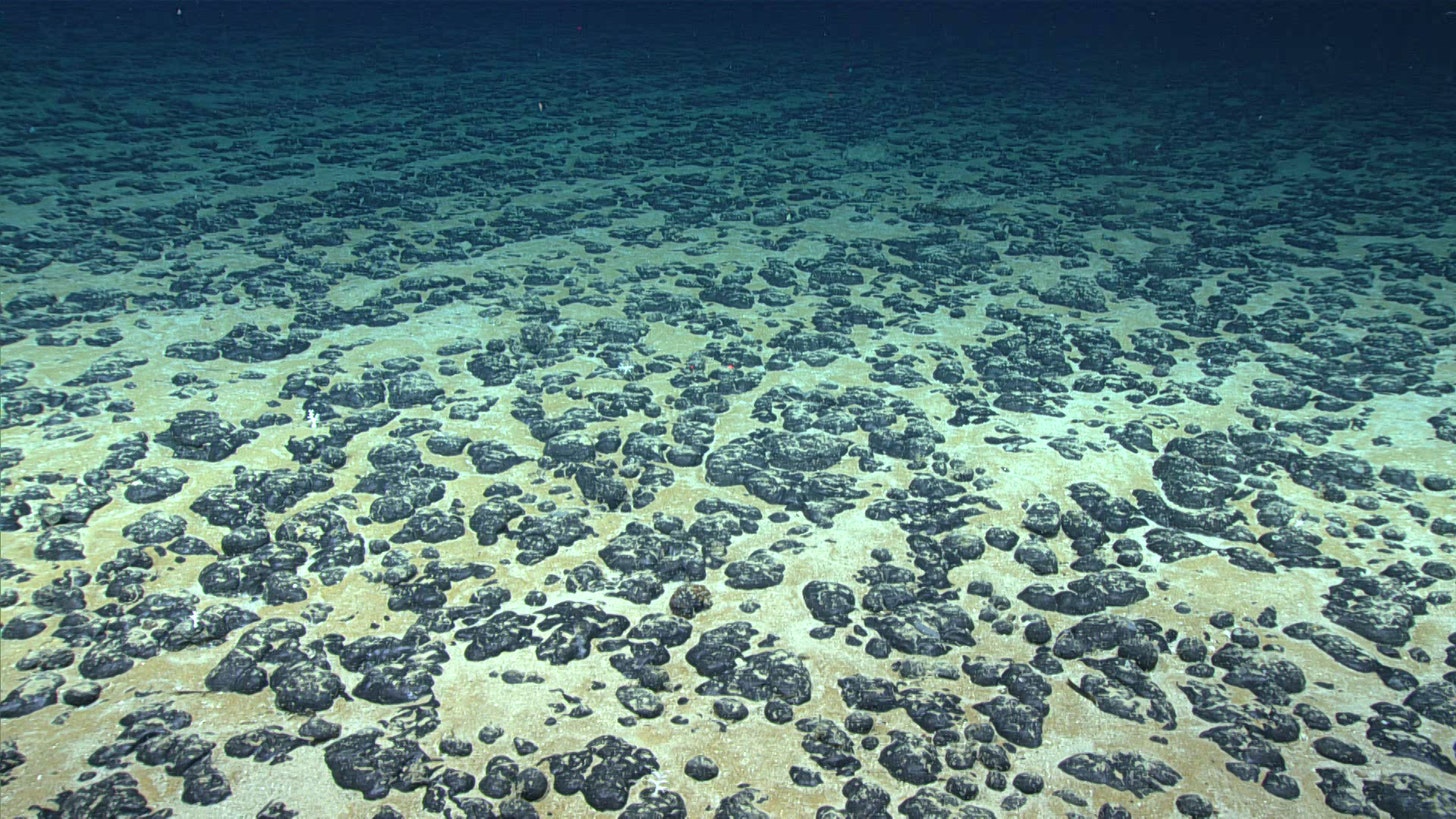

The targets of these companies are potato-sized rocks that scientists call polymetallic nodules. Sitting on the ocean floor, these prized clusters can take more than three million years to form. They are valuable because they are rich in manganese, copper, nickel, cobalt that are claimed to be essential for electrifying transport and decarbonizing the economy amid the green technological revolution that has emerged to counter the climate crisis.

To vacuum up these treasured chunks requires industrial extraction by massive excavators. Typically 30 times the weight of regular bulldozers, these machines are lifted by cranes over the sides of ships, then dropped miles underwater where they drive along the seafloor, suctioning up the rocks, crushing them and sending a slurry of crushed nodules and seabed sediments from 4,000-6,000 meters depth through a series of pipes to the vessel above. After separating out the minerals, the processed waters, sediment and mining ‘fines’ (small particles of the ground up nodule ore) are piped overboard, to depths as yet unclear.

But a growing number of marine biologists, ocean conservationists, government regulators and environmentally-conscious companies are sounding the alarm about a variety of environmental, food security, financial, and biodiversity concerns associated with seabed mining.

These critics worry whether the ships doing this mining will dump back into the sea the huge amounts of toxic-waste and sediments produced by grinding up and pumping the rocks to the surface, impacting larger fish further up the food chain such as tunas and contaminating the global seafood supply chain.

They also worry that the mining may be counterproductive in relation to climate change because it may in fact diminish the ocean floor’s distinct carbon sequestration capacity. Their concern is that in stirring up the ocean floor, the mining companies will release carbon into the environment undercutting some of the very benefits intended by switching to electric cars, wind turbines and long-life batteries.

Douglas McCauley, who is also the director of the Benioff Ocean Institute at the University of California Santa Barbara, warned against trying to counter the climate crisis with solutions that rely on a “paradigm of just ripping up a new part of the planet.” If the goal is to slow climate change, he said, it makes little sense to obliterate the deep-sea ecosystems and marine life that presently play a role in capturing and storing more carbon than all the world’s forests.

If the high seas represent the last frontier on earth, then the deep seabed outside of national waters is a frontier beyond that, a realm subject to a unique regime under international law, deeming the international seabed area and its resources to be managed by an international organization called the International Seabed Authority (ISA) on behalf of humankind as whole. “But who benefits and how from this new rush to seabed mining remains unclear,” said Kristina Gjerde, high seas policy advisor for the IUCN Global Marine Program. “And what constitutes benefits to humankind is also unclear as the deep seafloor is filled with untold biodiversity, much of it vitally important to the survival of our planet.”

Still, Nauru hopes to forge ahead with seabed mining. Located in Micronesia, northeast of Australia, the tiny island is among the smallest countries on the planet, with a landmass of 8 square miles and a population of around 12 thousand. By moving faster than its competition, this cash-strapped developing nation hopes to get an early edge on a potentially multi-billion dollar market even though Nauru itself is only likely to receive a small fraction of the financial benefits of seabed mining from the Canadian company it is sponsoring.

In June, Nauru took the first step in launching the industry. It announced plans to submit an application for commercial extraction on behalf of its sponsored entity “NORI” as early as 2023 to the International Seabed Authority. Such an application will be judged against whatever the deep sea mining rules are at that time — finalized or otherwise.

Over a dozen other countries, including Russia, the UK, India and China, have 15-year exploration contracts. The government of India has recently set aside $544 million to stoke private sector investments and technological research in this industry. But Nauru is taking the lead partially because its sponsored company NORI is a wholly owned subsidiary of a Canadian company that thinks it may benefit from being the first, based on its arguments that the minerals are necessary to enable the transition to a new green economy.

International interest in seabed mining has been stoked partly by new advances in robotics, computer mapping and underwater drilling — combined with historically high but fluctuating commodities prices. Mining companies globally are said to be scouring for fresh reserves, having depleted much of the world’s easy-to-access veins. The metals they seek are used in magnets, batteries, and electronic components for smartphones, wind turbines, fuel cells, hybrid cars, catalytic converters and other high-tech gadgetry. These metals are commonly found on land but some raise concerns that these may not be enough.

“With dwindling resources on land, with exponential growth of demand, and a shortage in circulation (recycling), there is a need to find alternative sources of critical metals needed to allow the energy transition to zero-net carbon economies,” said Bramley Murton, a marine researcher at the UK’s National Oceanography Centre. It has been estimated that, collectively, the nodules on the bottom of the ocean contain six times as much cobalt, three times as much nickel, and four times as much of the rare-earth metal yttrium as there is on land.

Mining companies and states have set their eyes on a specific part of the sea, an area bigger than the size of continental United States that stretches from Hawaii to Mexico, neighboring Nauru’s exclusive economic zone. The ocean floor under that area, known as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, is estimated to contain metals valued at between $8 trillion and $16 trillion.

Nauru has teamed up with NORI, which is owned by a Canada-based firm called The Metals Company to explore this area. “We are proud that Pacific nations have been leaders in the deep-sea minerals industry,” a statement co-authored by Nauru’s representative to the International Seabed Authority recently declared.

Scientists have conservatively estimated that each mining license will permit direct strip mining of some 8,000 square kilometers of seabed over the course of a 20 year mining license from the ISA and ‘easily’ impact a further 8,000-24,000 square kilometers of surrounding seabed life by sediment plumes generated by the mining the ocean floor. They estimate that the ‘nodule obligate species’ – the animals living on the nodules or, like deep-sea octopuses, that otherwise need the nodules to survive – will take millions of years to recover and even the animals living in the surrounding sediment may take hundreds to thousands of years to recover from the impact of mining.

Some corporate stakeholders are voicing skepticism. In March, BMW and Volvo Group, along with Samsung and Google, pledged to abstain from sourcing deep sea minerals. In its most recent global report, the International Energy Agency, a global body that advises countries on policy, concluded that seabed mining machines, “…often cause seafloor disturbance, which could alter deep sea habitats and release pollutants…stirring up fine sediments, could also affect ecosystems, which take a long time to recover.” In June, the European Parliament also asked the executive branch of the European Union to stop financing deepsea mining technology and called for a delay in more exploration operations.

UK House of Commons Environment Audit Committee in 2019 concluded that deep-sea mining would have “catastrophic impacts on the seafloor”, the International Seabed Authority benefiting from revenues from issuing mining licenses is “a clear conflict of interest” and that “the case for deep sea mining has not yet been made”

One worry among seabed mining critics is that the industry’s giant suction, grinding and harvesting machines will kick up huge and suffocating clouds of sediment both along the seabed and high in the water column that block light, crowd out oxygen, produce harmful amounts of noise pollution and disperse toxins which decimate life and contaminate seafood. Such contamination could also pose a threat to the food security for developing and coastal nations whose fishing stocks and other seafloor marine life would be decimated.

“We need much more time for research to be carried out, not by mining companies, but by independent seabed ecologists,” said Kelvin Passfield, who runs the Te Ipukarea Society in the Cook Islands and is part of a group of non-profit organizations in Fiji, Vanuatu and elsewhere in the Pacific islands that are concerned about the impacts of such plumes on local fishermen and food security.

Other critics see the mining as a ponzi scheme of sorts that is meant to draw venture capital investment but in fact has little real chance to make money in the long term. Matthew Gianni, co-founder of the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, said that seabed mining companies are trying to peddle a false choice between having to mine cobalt and nickel on land or in the deep sea when they claim we need 100s of million of tons of these metals to build batteries for electric vehicles and other renewable energy storage technologies. “We don’t need to build batteries with either nickel or cobalt. Tesla and BYD, the world’s second largest EV manufacturer, are making cars with Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) batteries, with little to no nickel or cobalt, which are selling unexpectedly well,” he said. “There is massive investment now being put into developing batteries that don’t use these metals at all.” Better product design, recycling and reuse of metals already in circulation, urban mining, and other ‘circular’ economy initiatives can vastly reduce the need for new sources of metals, he said.

Once thought to be relatively lifeless, the deep sea is now seen by most scientists as a species-rich environment populated by creatures that thrive under conditions that seem impossibly extreme. And yet, much of its biodiversity on the seafloor is distinctly vulnerable to change because their habitat is so far removed and thus rarely disturbed.

The oceans already face a daunting list of threats, ranging from overfishing, sonar testing, oil dumping, and plastic pollution, to sea level and temperature rise, acidification, oxygen depletion, algal blooms, and ghost nets. Add to those the additional strains faced by deep-sea marine life on the seafloor: internet cables, bottom trawling, treasure hunting, oil and gas drilling, coral bleaching, the sinking of retired drilling rigs. In 2019 the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) issued its Global Assessment report which estimated that a million species are at risk of extinction, many within the next several decades unless we reverse the drivers of biodiversity loss.

One of the biggest challenges in stoking concern about this type of mining is that the seabed is so far removed — geographically, emotionally and intellectually — from the public that benefits from it. Most of the world’s seafloor is not even mapped but less properly or fully understood or robustly governed. Deep below the waterline it is always dark, its many of its inhabitants defy categorizations into the traditional animal-plant-mineral taxonomy.

No solution to a problem as complex as the climate crisis will come without difficult decisions and heavy costs especially as the global public tries to wean itself from fossil fuels.

The hard part, though, is figuring out how to take one step forward without also moving three steps back.